Teaching and Learning as a Common Act

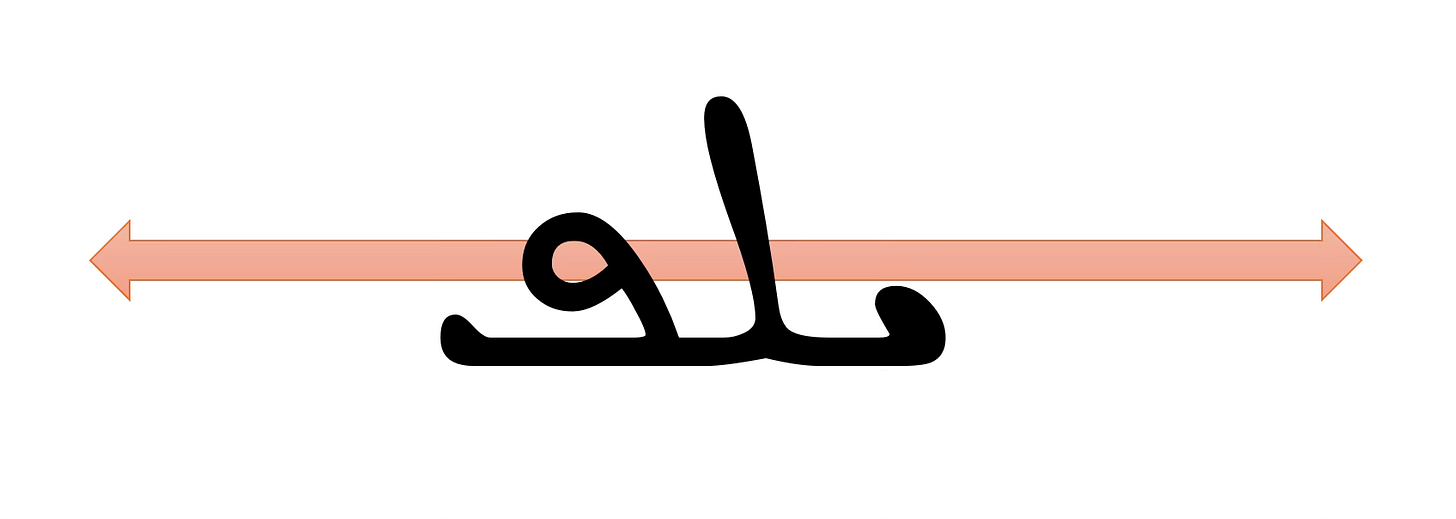

Process over Outcome in Teaching in Light of the Syriac Root [ܝܠܦ] That’s Learning and Teaching at the Same Time

In the ancient Aramaic dialect of Syriac, a single root— ܝܠܦYLP—carries a profound paradox, meaning both "to learn" and "to teach." One word, two meanings. Like a fork that’s also a spoon. From this root spring two words: yālūphā (student) and malphānā (teacher). It’s like they’re twins, but one’s got a mustache. These terms, sharing the same linguistic DNA, reveal a truth often overlooked: teaching and learning are not distant cousins but intimate partners in a timeless dance. Yet, in modern contexts, we rarely pause to notice the cues that bind them so closely together. The point is, teaching and learning are supposed to be this tight-knit thing, but most people don’t notice. (I don’t blame them. I’m still trying to figure out why my toaster keeps winking at me.)

The Syriac Root YLP: A Linguistic Mirror

Syriac, a language steeped in the heritage of early Christian and Middle Eastern traditions, often encodes wisdom in its morphology. The root YLP (ܝܠܦ) is a perfect example. Its core meaning revolves around the acquisition and transmission of knowledge. In its base form, it means to learn is to absorb, to internalize, to grow—like when you finally figure out how to open a pickle jar. In its amplified form, it means to teach, to guide, to impart, to nurture, like when you show someone else how to wrestle that jar lid. The beauty lies in their shared origin: YLP doesn't distinguish between the two acts as separate endeavors but as facets of the same process.

From YLP, we get yālūphā (ܝܠܘܦܐ), the student, the one who learns (no, not Chalupa… sorry for all the Taco Bell references). That’s the guy sitting there, staring at a book, wondering if it’s too late to become a professional napper. The word evokes humility, openness, and a readiness to receive. Meanwhile, malphānā (ܡܠܦܢܐ), the teacher, derives from the same root but with a prefix (ma-) that suggests agency, one who facilitates learning, like it’s trying to sound official. “I’m not just teaching, I’m ma-teaching.” In Syriac, the student and teacher are not opposites but complementary roles, each defined by their relationship to YLP’s core act of knowledge exchange.

Teaching and Learning: Same Team, Different Jerseys

This linguistic unity mirrors a deeper truth: teaching and learning are inseparable. They are like socks and feet. You don’t really have one without the other (unless you’re okay with blisters—but I guess we have all had the blister-making experience in the classroom). A teacher is only as effective as their ability to learn—from their students, their subject, and the world around them. In my preparation, I find myself relearning old material and learning little details I never connected with during the first pass. A student, in turn, learns not just by receiving but by engaging, questioning, and even teaching others. The classroom, whether formal or metaphorical, is a space where both roles blur. A teacher might learn a new perspective from a student’s question; a student might teach a peer by explaining a concept in their own words.

But nobody sees it that way. We act like teaching’s a one-way street and learning’s just sitting there, taking notes. This view creates hierarchies that obscure the reciprocity at the heart of YLP. In reality, the best educators are perpetual learners, and the most engaged students are already teaching in subtle ways—through dialogue, curiosity, or example.

Why Nobody Notices

People miss this because life’s distracting—call them cultural or systemic habits. Modern education systems, with their emphasis on standardized testing and rigid roles, often prioritize outcomes over process. Teachers are judged by how well they deliver curricula, students by how well they absorb it. Little space remains for the organic interplay that YLP suggests. Outside the classroom, we see similar patterns: mentors are expected to have all the answers, and learners are rarely encouraged to see themselves as contributors to the knowledge ecosystem.

Plus, English doesn’t help. “Teacher” and “student” sound like they met at a bus stop and never spoke again; they share no etymological root. Contrast this with Syriac, where yālūphā and malphānā are visibly tethered to YLP, reminding speakers that learning and teaching are two sides of the same coin. In English, it’s like they’re from different planets. Without such linguistic cues, we’re less likely to notice the mutual dependence of these roles.

The Syriac root YLP offers a subtle but powerful reminder: teaching and learning are not just related—they are intertwined. The yālūphā and the malphānā are not fixed identities but roles we all play at different moments. By paying attention to this ancient linguistic wisdom, we can rediscover the joy of knowledge as a shared journey, one where every step forward is a step together.

Now, did I teach you something or did I learn not to babble on without my morning coffee?